Art Collector’s Guide

What You Don’t Know About Authentic Impressionism

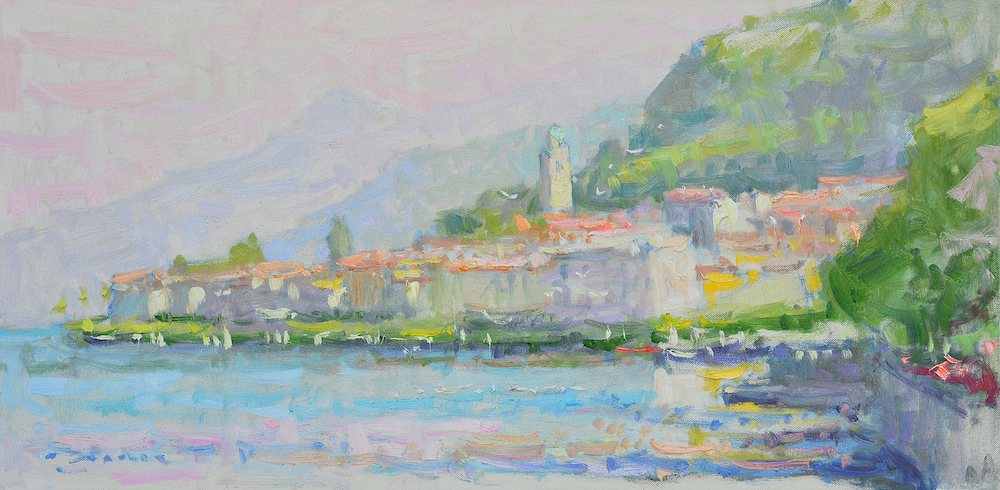

To the left is a recent painting (“On A Dreamy Afternoon”) of mine. I work within the tradition of French Impressionism.[i] Yet I am reluctant to call myself an Impressionist for the simple reason that in the year 2020 a painter doing Impressionism will be thought of by elites in the world of visual art as someone whose work is derivative and chocolate boxy. Worse, perhaps, I would be thought of as someone who is clueless as to the advances – pointed to, of course, by these same elites in visual art – during the hundred and forty-six years since the Impressionist held their first exhibition in 1874. The cognoscenti, however, are polite. They would simply dismiss me and my work out of hand as unfashionable.

Fair enough. I can accept that. Besides, unfashionable in some circles is often quite fashionable in others. But I am also convinced that the challenge of sincerity posed to the art world by a handful of Parisian painters in 1874 is as relevant now as it was then. Therefore, I have chosen a different appellation. I am an authentic Impressionist.

Let’s begin with a brief summary of the story of the painters who became known as the French Impressionists and in whose tradition I work.

Where

Paris, the center of western culture during the 19th century and into the 20th century.

Who

The names you will find most often associated with French Impressionism are Gustave Caillebotte, Mary Cassatt, Paul Cezanne, Frèdèric Bazille, Edgar Degas, Èdouard Manet, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley, all of whom came of age in the late-19th century.

However, in explaining the philosophy and practice of the movement known as French Impressionism or what I have been calling authentic Impressionism, I shall focus on Pissarro, Cèzanne, Monet, and Degas[ii], given that they left behind the most developed thoughts on what was considered a new approach to painting. In terms of the work itself that I will show you, these same painters plus Morisot are, perhaps, the most emblematic of the kind of work that issued from this new approach.

When

The period during which the French Impressionist dominated Paris, strictly and narrowly, can be bracketed by the first and last of their eight independent exhibitions. The first of these independent exhibitions took place in April-May 1874, while the last was held in May-June 1886. Some of the Impressionists lived well into the 20th century and their influence impacted painting around the world. So it is not uncommon to find celebrated Russian Impressionists or American Impressionists working in the early part of the 20th century, for example. But before we can understand French Impressionists and what makes their work distinctive, we need to know what independence meant to them and why it was so important. It is this part of the story that is the least understood and the most revealing.

What: A Special Kind Of Freedom

The French Revolution, which took place in 1789, led to the abolition of absolute monarchy. But the stranglehold by the aristocracy over art education and the all-important career-making exhibitions of the Salon de Paris persisted late into the 19th century. The painters that would become known as the Impressionists were artists in a long line of painters who since the French Revolution pressed repeatedly for control over the making and exhibition of their work. With the aristocracy greatly weakened through war and political uprisings, particularly in Paris, the Impressionists, known initially as the Intransigents, launched a series of exhibitions independent of the Salon. It was by means of these independent exhibitions that our merry band of reluctant rebels achieved the long sought-after goal: they had absolute control over their art making, democratic control over the organization of their exhibitions, and established, for the first time, “a direct relation with the public.” The Salon de Paris, steadily displaced by private galleries, agents, and exhibitions, by 1890, never was to recover its prestige or authority.

We shall delve further into the “what” as we actually examine the work of these painters, but in order to do that we need to look more closely at “why.” It’s a story all artists ought to know.

Why: “There’s no sincerity.”

In 1862, a 22-year old Monet was studying in the atelier of Charles Gleyre, along with Renoir, Sisley, and Bazille. Gleyre had garnered notable success at the Salon early in his career. Having the opportunity to study with him, then, presented an opportunity in the conventional sense: the opportunity for an artist to make painting a career. There were no other similar opportunities.

But then an astonishing thing happened. Monet suddenly urged his fellow artists to revolt. But why? What had gone wrong? The event that triggered Monet’s abrupt dissatisfaction was a critique that Gleyre had given him. Gleyre had told the young Monet that he had made a stocky model look stocky. “But he is stocky,” said Monet. “True, but that is ugly,” warned the master; “Moreover, you have made his foot too large.” Again Monet, “But his foot is large.” Gleyre cautioned Monet that if he wished to be juried favorably into Salon exhibitions, he “must think of the works of antiquity.” Keep in mind that a young student’s future patronage, in that moment, turned on his (and it was mostly his) ability to glorify powerful political and religious figures, their military campaigns, stories in the literature they favored, as well as their feet and bodies – large and stocky notwithstanding. Monet’s response: “Let’s get out of here. The place is unhealthy. There is no sincerity.”

Here we come to the very heart of the philosophy of authentic Impressionism. Consider the concept of “unhealthy” in this context. Monet was articulating the notion that while he and his compatriots dreamed of a painting career, it would only make sense if in that career they could be free to become more of who they already were. If career meant that they would become the picture-making instruments of someone else, they would never discover their own individual and distinct abilities, or what moved each of them differently, or know the means of expression they would each invent and employ for themselves. They would never know in their lifetime who they were most. At 22, Monet knew he would never have the opportunity to become Monet. That’s what was unhealthy. That is why Monet believed that there was no sincerity in the studios teaching painters to become Salon art stars.

Naturally, this point of view was understood by art system elites then as subversive. It meant that while the selling of paintings might be a business, particularly in light of the growing “bourgeois” economy, as it was called, the making of paintings was not and never could be. The reward was in the work, Cèzanne would implore, never in adjusting one’s natural aesthetic proclivities in order to capture a career advancing “opportunity.” Competitions were derided for the same reason. Respecting the dictates of juries entirely divorced from each artist’s personal unfolding, as it were, only diminished the control over their work that they sought. Not that members of the group did not pursue a variety of exhibition venues. They did, compelled too often, but they were shrewd about it and clear. Monet, for example, referring to a painting he was submitting to the Salon in 1880 acknowledged, “This is not Monet.” Pissarro felt that were he to exhibit at the Salon he would have to “make too many concessions, thus sacrificing the honor of his cause.”[iii] But the direction and the value they consistently prioritized and the one that explained their approach to painting was that of self-direction.

What Distinguishes Authentic Impressionism In The Work Itself

Before I show you examples (primarily details of larger paintings) of their work and mine, there is a last link in the chain that completes the circle and that is you. The Impressionists sought and obtained a “direct relationship with the public” because they wanted to pass onto the viewer the experience they had while making the work. Degas noted, for example, that “Drawing is not what one sees but what one can make others see.” And Cézanne: our methods are only “simple means for us to make the public feel what we feel.” Keep in mind that this transfer of feeling, were we to paint to please juries or agents, would eventually be eroded. This is precisely what Degas had in mind when he recalled the shared sensibility of the serious artists of his generation: “In my day, people didn’t ‘succeed.’”

Below I have listed a few distinguishing features of authentic Impressionism but not all. For example, the role that a sense of atmosphere plays – particularly in the work of Monet and Cézanne – would require a considerably longer essay to explain.

- 1. We do not make pictures of things; we make visual experiences

- 2. We are moved by and feel “sensations”

- 3. We avoid literal precision

- 4. We paint in layers

- 5. A process of becoming

“No tasks, no tasks.” This was an admonition articulated by several in the group including Manet who early on was considered the group’s thought leader. This meant that painting should serve no external purpose, should not refer to the subject matter for its meaning or beauty. Making paintings with social commentary or paintings that depended on iconic figures for its ability to project feelings was viewed by Pissarro, as Joachim Pissarro (great grandson of the painter) reports, as nothing short of “aesthetic slavery.”

This is a huge shift in the understanding of what the activity of painting could be all about and, I might add, this shift is still not grasped, I would argue, by scholars writing today who mistakenly assume that painters, then and now, are akin to human cameras and picture-making journalists or sociologists. As odd as it may sound, we do not make pictures of things, even though a picture may result. We are visual artists and because of this we are not indifferent to visual stimuli such as line and color. In fact, because we are moved, essentially, by the visual elements that we see, it is best, then, that we not see the thing as a thing with a name but rather the visual elements of which the thing is composed.

You are not a painter if you don’t love painting more than anything else; but it is not enough to know your métier, you must also be moved. – Manet

Moved by visual elements, to be more specific. In other words, I may feel nostalgia when looking at my childhood home or loneliness in walking alone on a beach. But this isn’t what Manet is getting at. The visual elements that we respond to are sensations of color and line which, as stimuli, possess us. This oneness with nature is part of the sensation of feeling larger and, as our brush touches the canvas, we are propelled into a new realm of perception. So necessary is this metamorphosis to the activity of painting that it requires, as Monet instructed, that we do not see the thing before us. Just see little pieces of color. This means I must get past seeing things with names, like tree, house, person. Paint the head as you would a doorknob, advised Cézanne.

I live on Lake Como. And because my intention is not to make pictures of the lake, my challenge is to avoid the beauty of the lake that is horribly obvious to everyone! How can I get past that? How can I escape into a realm, where the lake as a lake not only disappears but the lake just as line and color begins to possess me?

Learning to see just the sensations of light provides the answer. And so I enter into a ritual: I must escape from the normal realm of perception by breaking my vision into visual pieces. These pieces of color stir feelings within me. My effort to mix these colors through an orchestration of varied brushstrokes completes who I am in that moment.

In the painting above which I did on Lake Como, yes, there is the lake and buildings, but look again (at image below) through the eyes of someone trained to see past the facts of the lake and buildings; it becomes possible to actually see the vibrating sensual pieces of nature that we call line in some instances and color in others.

Color first. Lake and buildings second. I pulled out little pieces of color that I actually did see and placed them in a way that they vibrate off the canvas, carry, and mix optically at a distance. The intention here is to make a painting where the brush strokes of paint feel like the sensations of light that moved me. “Impressionism,” said Monet, “is only direct sensation.”

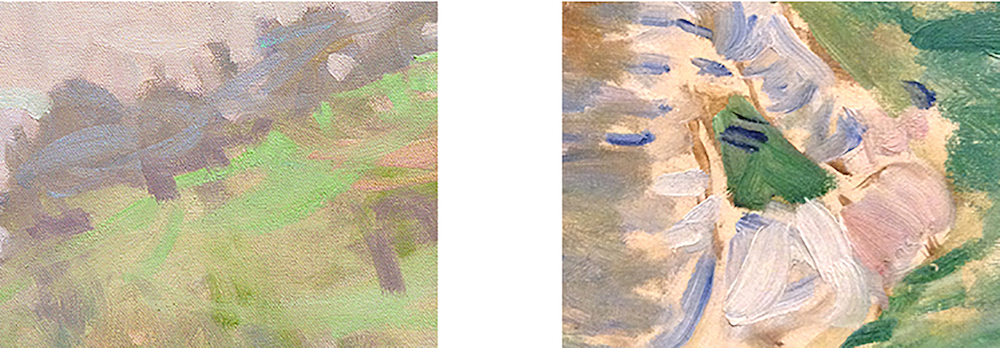

Below we find Monet making marks that enable viewers of his work to feel the light that moved him.

Degas (below) responding to the sensations of nature (models) in the studio.

Morisot (below), not seeing people or a bench but the sensations of light reflecting from human figures, uses emotive brushwork to give you the experience she had.

An example of a picture that is literally precise is a photograph. As noted previously, we do not want our paintings to refer to or depend upon the subject matter for its emotional impact, we rely on a variety of visual elements to both express and evoke feelings. The brush stroke may be the most important of these elements for brush strokes are the language of feelings that the painter realizes.

Sometimes we caress the canvas; at other times we attack the canvas. Brush strokes are extensions of the liveliness of nature, a nature as source. Varied and raw, they transfer to the viewer the feeling of pure presence that the painter had. Authentic Impressionist paintings, therefore, aren’t about finish. We are not baking cakes or making something the value of which is determined by some external standard called “finished.” The value of a painting are the feelings we had as we made it. Paintings are alive at any point in time. Just as we would not say that a 10-year old is unfinished and therefore unworthy of our attention, we would not say that the Morisot painting shown previously is incomplete and would hold more value were we to make it more literal.

Below is a detail from one of Monet’s water lilies. The painting is not about water lilies. They are the prompt. It’s about the feelings that Monet newly realizes as he stands before nature in what he called a posture of “total self-surrender.” Authentic Impressionists straddle two realms of sensations: the realm of the prompt or the subject matter and the realm of emotion that he or she wishes to render and make visible for the world to see and feel as well.

In my painting below, the prompt was lake, boats, and buildings. My purpose in surrendering to the sensations of my vision was to get captured and propelled into a realm where I am moved and able to move someone else.

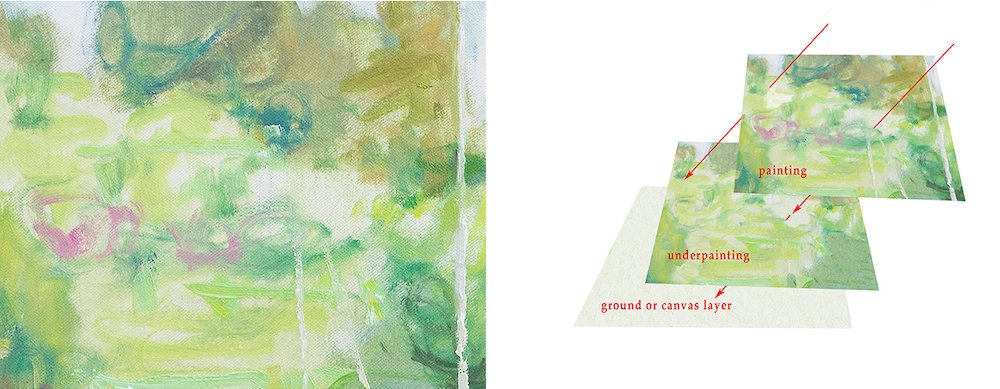

You may have noticed that these paintings are painted in layers. For example, let me take a detail of the painting in the previous page to illustrate what I mean.

On the left (above) is the detail and it enables us to look more closely at a section of the painting in question. On the right is a diagram showing how the painting was painted in layers. The top layer is the final layer or painting. The layer under the top layer is the underpainting and the bottom layer is the canvas. Now, understand that the use of three layers would be the simplest version; Monet used dozens of layers, but the virtue of this construction is that it allows the viewer to look down into the painting and past the surface layer, sometimes all the way down to what is called the ground or actual canvas. This gives the viewer a sense of space, almost 3D like. Lines and color tangle, adding a sense of movement or freshness along with depth.

Above are two details of the paintings you have already seen. Note how lively brush strokes sit on top of brush strokes below and, in the case of Morisot, we see down to the canvas itself. It is obvious, particularly in the case of Morisot, that she is not seeing a little girl but the sensations of line and color that compose the little girl. We can feel, by her marks, how she was moved, how nature touched her.

Meyer Shapiro, an important scholar of visual art, said that the longer he looked at the work of Manet and the Impressionists the more he understood that their accomplishment was “to preserve painting – as a practice, a set of possibilities, a dream of freedom.” This is the essence of authentic Impressionism. The activity permits us to express our feelings and realize new ones that could not have been possible had we not made those marks. There is an unfolding, a self-creation, a becoming that is the single most important motivation for an authentic Impressionist. Which is not to say that we are not interested in sales and security. Of course we are. But not at the expense of becoming who we are most.

This particular understanding of freedom as a process of becoming was stated nicely by Cézanne who wrote, “Every time I stand in front of my easel, I am another man, and always Cezanne.” He is saying that with every painting he grows a little, and in some small way, he is another man. And yet, he is always Cézanne.

But this type of freedom, linked all the way back to the need for self-direction in terms of independent exhibitions, is not easily grasped in our culture today because the emphasis is on the process, less so on the painting, which merely happens along the way.

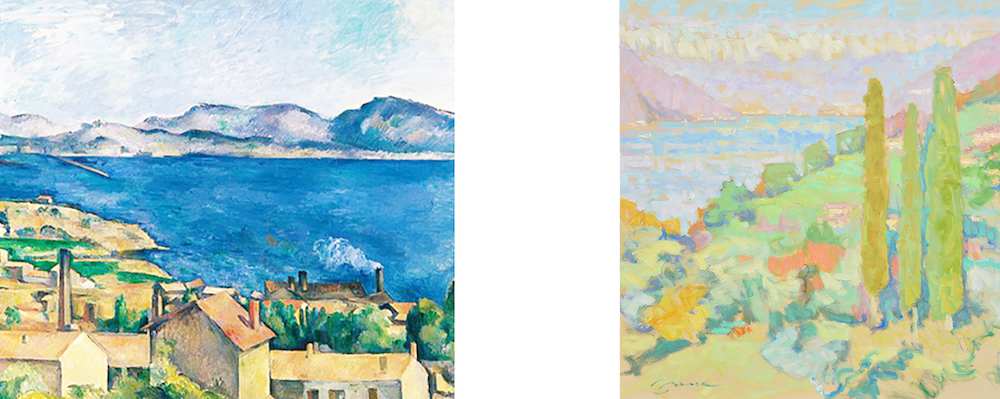

For example, the painting on the left above is by Cézanne, the one on the right is by me. Cézanne’s painting looks as though it may not be Impressionist work. It seems a little flatter. There is less overt vigorous brushwork than someone like Morisot. His work generally does not employ the bright colors that we find in Monet or Degas’ work. For reasons having to do with the Cézanne product, then, scholars have consistently declared Cézanne a Post-Impressionist. Yet Cézanne was born before Monet, exhibited with the Impressionists, studied with Pissarro, and he himself identified with the group, saying at one point, “For an Impressionist to paint from nature is not to paint the subject but to realize sensations.” He also offered this Impressionist admonishment: “The artist must be a laborer in his art and discover early on his means of realization…It all comes down to this: to have sensations and to read nature.”

Authentic Impressionism turns, then, not on the result of the process (i.e., the product) but the process itself that issues in becoming. So the distinctive features of authentic Impressionism outlined above are likely, maybe probable, but not determinant. When we render our feelings sincerely by making marks on a canvas, those marks are a manifestation and a completion of who we are in that moment, as we have seen. The process puts us on our original path. Because of this, it is easy to distinguish the work of one Impressionist from the next and probably most easily in distinguishing the work of Cézanne from the others. Yet given their approach, their self-understanding, they were Impressionists all.

If truth be told, the “what” of Impressionism was not the independent exhibitions or even the “new painting.” Rather, the “what” of Impressionism” was and is the new painter, a painter committed not to the production of canvases or even the finishing of them, but to the process of becoming that is part of the making of them. The “why” of sincerity explains the “what” of independence.

And the Viewer

In this mode of painting, I wish to make paintings that refer to nothing. The boats, the trees, or houses are merely prompts or points of departure. I want the viewer of my work to feel something of the sensations I felt when I made it. The need to have work of this nature in one’s home is not the need for decoration or the need to have a ready chocolate box at hand. Rather, it is to have a continuous source of pure presence and of exhilaration. It is to have a way to get caught up and carried away, always. It is to have access to a mood of fullness or liveliness, or of plenitude. Think of a painting not as an object but as a state of interactive fascination that propels you into a crossing, a metamorphosis, a becoming. You, as the viewer, can have a similar experience as I did when I made the painting. Hence, the virtue of collecting art that moves you.

A well-known painter by the name of Vibert ran into Degas in a museum one day. Anxious to have Degas visit his exhibition, Vibert implored, “You must come to see our exhibition of water colors. You may find our frames and rugs a little too fancy for you, but art is always a luxury, isn’t it?

“Yours, perhaps, “ retorted Degas, “but mine are an absolute necessity.”

—

[i] I studied primarily in the studio of William Schultz. Schultz’s primary teacher was Robert Brackman. Brackman studied with Robert Henri for a time and Henri studied in Paris in the 1880s. Brackman also studied with Ivan Olinsky who was a student of John Singer Sargent. Sargent in turn was close to the French Impressionists, especially Monet. I also studied briefly with Wolf Kahn who was a student of Hans Hoffman.

[ii] Degas inveighed against the spontaneity of Impressionism and at other times he complained that his serious eye problems made working out of doors impossible. Yet he worked from nature indoors and from memory. “I would rather do nothing than do a rough sketch without having looked at anything.”

[iii] As reported by his great-grandson Joachim Pissarro, Monet and the Mediterranean, p. 19.

Address

Via Teresio Olivelli, 20

22021 Bellagio (CO)

Italy

+39 338 975 7135

Open Hours

Tuesday - Saturday: 11:00am – 6:00pm

Sunday - Monday: 1:00pm – 6:00pm